2009 Corvette ZR1: Ruthless Pursuit of Power: Supercharged Edition - Page 2 of 7

|

|

Page 2 of 7

© 2008 by Hib Halverson

No use without permission, All Rights Reserved

![]() Discuss this article

Discuss this article

Seven Liters are Nice but I'd Rather be Blown

It's the LS9's visual center of gravity, so we'll start at the top: with the blower. Displacement of modern Vette engines peaked in 2006 with the introduction of the 427 cubic inch, 7100-rpm, 505-hp LS7. Going forward, with LS9, the '09 Cadillac CTS-V's, 556-horse LSA and (since only fools believe GM could justify these engines' development costs without some other, higher volume application coming in the future) a likely variant for light and/or medium duty trucks, the substitute for cubic inches will be supercharging. From a power perspective, it makes small engines big and, from a fuel economy perspective, it makes powerful engines small. From here on, boost is the only way we'll get the performance we expect from engines in "super" Vettes and, even that, that will be as long as government doesn't regulate CO2 emissions beyond a reduction which results from the new CAFE. If that happens, Vettes in the mid-2010s might end up rebadged, next generation Sky roadsters with V6 turbos.

While the 3rd gen. ZR1's early prototype, the original "Blue Devil", had two turbochargers, the program didn't get far before GM Powertrain decided Eaton Corporation's engine-driven, "modified Roots" supercharger was a better choice for several reasons: 1) it eliminated the complex twin-turbo configuration, 2) boost response is nearly instantaneous, i.e.: no lag. 3) GMPT did proof-of-concept (POC) work with an LS2 fitted with an Eaton, M122, fifth generation supercharger (currently in production on the Cadillac XLR-V and sold in aftermarket C5/C6 versions) which demonstrated that a Roots blown engine was promising and 4) Eaton tipped off GM that it was developing a sixth generation supercharger platform. Called "Twin Vortices Series" (TVS), this new blower family had projected efficiency improvements which would enable it to exceed the performance of M-series units and, more importantly, result in a smaller package.

Other engine driven blower choices, a centrifugal supercharger or a screw compressor, didn't make the cut. Centrifugals while popular with the aftermarket, have a less desirable boost curve and present an even more difficult packaging challenge. A screw-type supercharger wasn't the best choice, either. "In this application," GMs Yoon Lee told the Corvette Action Center, "With the engine displacement and the relatively low pressure ratios needed to achieve the power we wanted, this Roots blower is a better match. Screw compressors tend to be good if you want higher pressure ratios. In this case, again, the Roots is better."

"With the generation six supercharger," Ron Meegan added, "Eaton has improved the isentropic efficiency (see sidebar) to where its approaching the same level you would see in a screw compressor. Plus, with a screw compressor, you have to put a clutch on it. When you add that, the Roots comes out to be a little cheaper."

"To reduce parasitic loss," Lee explained, "you have to declutch a screw compressor at part throttle. Also, with screw compressors, rotor machining tends to be more intricate than with a Roots, so there's some extra cost there, too."

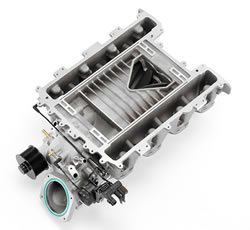

The LS9 induction system is a amazing packaging and performance accomplishment by a team headed by our pal, Mr. Lee. CAC readers may be familiar with his work from our coverage of the LS2 and LS3 intake assemblies in previous articles.

|

|

| One problem with the fifth-generation Eaton blower was architecture better suited to front-drive cars with transverse engines, such as this supercharged 3800 Series III V6 in a 2006 Monte Carlo SS. Image: GM Powertrain |

Another spiffy Eaton installation developed by GM Powertrain and the hot rodders under Chief Engineer John Heinricy at the GM Performance Division was the short-lived, Chevy Cobalt SS Supercharged. Again, the Eaton blower being well-suited to a transverse engine application made it a great match for the Ecotec inline four. Image: GM Powertrain |

The Eaton blower dates to a Ford, rear-drive-V6 application of 20 years ago. Later, it became common on performance oriented, GM, transverse engines recently the supercharged, 3800 Series III V6 in the '04-'05 Monte Carlo SS and the blown two-liter Ecotec in the '06-'07 Cobalt SS which have the blower drive at one side of the supercharger, the intake at the other and the outlet on the bottom. While that packaging makes sense on a sideways motor in a front driver with a low hood; it doesn't work well for a rear drive car because, with the blower drive at the front and the intake at the back, you either turn the blower around and run it with a jackshaft, as do some aftermarket systems, or you add ducts to move air to the rear of the engine, like on the 4.4L V8 in the XLR-V.

The Eaton TVS, of which the LS9 and it's less powerful sibling, LSA, are the first O.E. applications, sets new standards for engine driven superchargers on gasoline engines in production vehicles. A key enabler of the packaging which resulted in the LS9 is a specific case for the R2300, 2.3-liter, TVS supercharger. It has a front intake, slightly left and below the drive rotor's shaft, and a top exhaust, a configuration needing neither a jackshaft nor complex ducting.

"We've had concepts for that floating around for several years," Eaton's Grant Terry told us. "The goal is a much easier path for the air to get into the supercharger, On a north-south engine installation for rearwheel drive, typically, you bring the air into the back of the supercharger, but you get induction losses by doing that. You're turning the air depending where your airbox is as much as 270° to get into the back of the supercharger. Our goal was a straight shot into the inlet. The front inlet design meant a whole different way of assembling the supercharger.

"When they (GM Powertrain) looked at (the front inlet), they were having trouble trying to package the '156 rear inlet' (a prototype, 5th gen Eaton briefly considered for LS9). It solved a lot of big headaches for them in getting the blower onto this engine."

|

|